When footnotes have twinkletoes

Or, wit where you least expect it

Wit1 in the footnotes2 is like3 laughter4 in the library5:6 A7 joyful8 thing9 in an unexpected10 place.11 Is12 it a surprise13 or an14 interruption?15 It depends16 on whether you find God17 or the18 devil19 in20 the21 details.22

Defined, as always, as surprising creativity.

Substack has footnotes now! In the 1990s, it was thought that the hyperlink would kill the footnote. Oh, the 1990s.

Speaking of metaphors, here’s Noel Coward: “Having to read footnotes resembles having to go downstairs to answer the door while in the midst of making love.”

If you’ve got references to cite, please hide them in the endnotes and stop interrupting amorous playwrights! Only ring that doorbell if you’ve got an aside or a digression.

To get all categorical: An aside offers a snappy comment on the above text. It’s like speaking sotto voce, leaning over to the reader with a behind-the-scenes note.

I couldn’t say this in the actual text, but since we’re here in the relative anonymity of the bottom of the page, I’ll spill: This colon began life as an em-dash!

Edward Gibbon, the father of more than 8,000 footnotes in his gigantic History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, offered little asides at his subjects like, “M. de Voltaire, unsupported by either fact or probability, has generously bestowed the Canary Islands on the Roman empire.”

A digression, on the other foot, is how the author shoehorns in an irrelevant but still interesting observation.

“There is no good word for stomach; just as there is no good word for girlfriend. Stomach is to girlfriend as belly is to lover, and as abdomen is to consort, and as middle is to petite amie.” So wrote Nicholson Baker in a footnote in The Mezzanine, his 1990 novella about an uneventful escalator ride.

When writers get footloose with the footnotes, it becomes clear that author and typesetter are not on the same page.

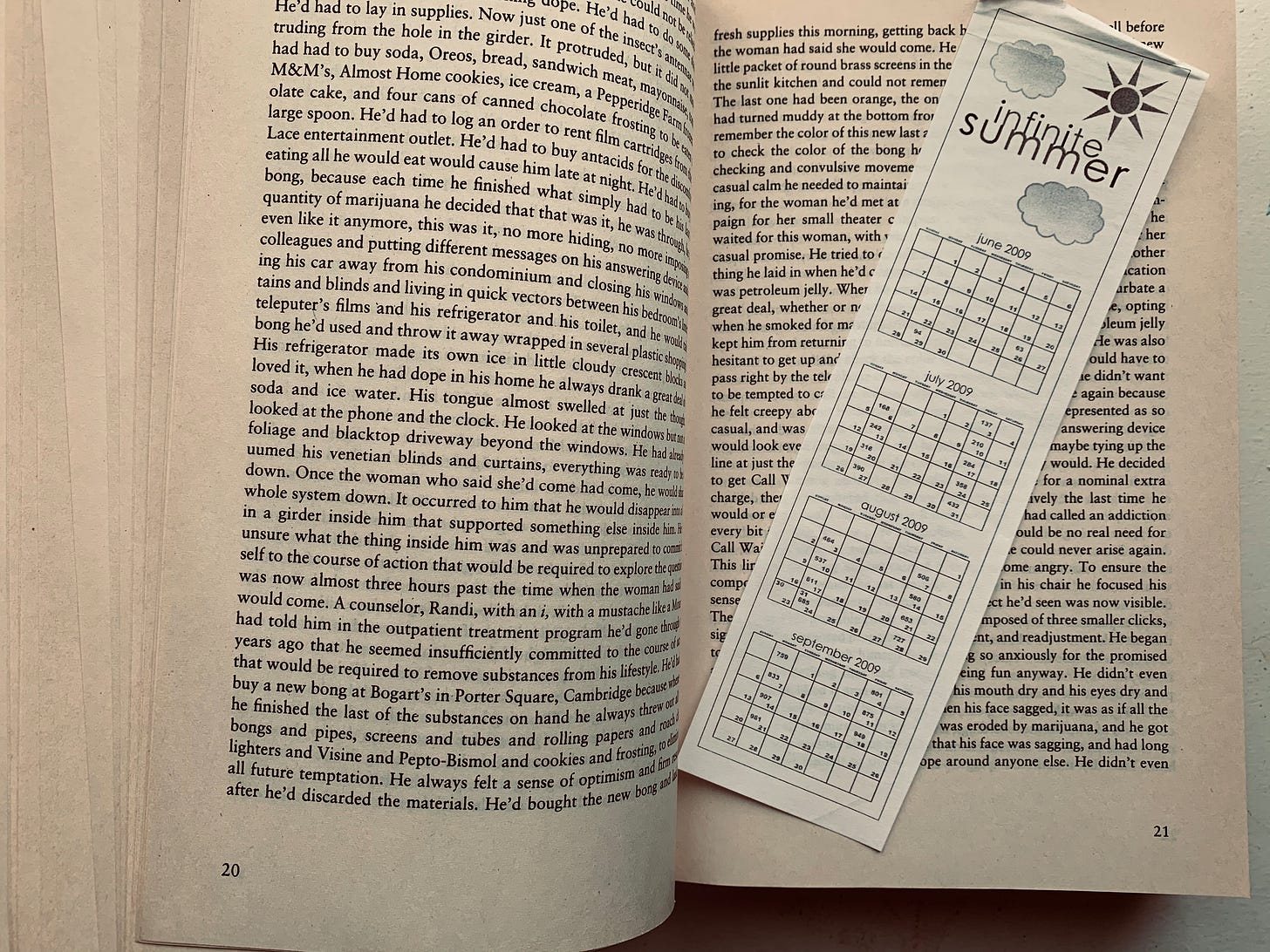

Which is why you need two bookmarks to read David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest. Because all the footnotes are endnotes!

Aside: I haven’t read Infinite Jest, and not for lack of bookmarks. I last tried in 2009 and got to page 21; pics and it didn’t happen:

But clearly the DFW to read this week, given the death of Limbaugh, is his 2005 footnote-perfect Atlantic piece on talk radio. They’ve done a decent job transferring the colour-coded experience to the web here.

Also, The Mezzanine is a mere 135 pages. But hey, what’s the hurry?

To appreciate footnotes, you can’t be pressed for time. A good footnote is a welcome distraction from the text. If your purpose in reading is pure data extraction, then be boring and stay on target. But if it’s more like a rambling walk on which you might stop to read a historical plaque or chat with a neighbour, then getting there is all the fun.

A better metaphor is an entertaining dinner guest. If their stories are filled with asides and digressions, all the better. You didn’t invite them over to extract information.

Unless you did, in which case, what are you, the Stasi? And the food better be amazing.

The best footnotes are self-contained aphorisms: Brief, irrelevant, irreverent, memorable. And on this number, Will Cuppy was the master. His 1950 riff on Gibbon, The Decline And Fall of Practically Everybody, featured such factual gems as:

“Charlemagne handled his great sword beautifully in parades. For reasons best known to himself, he never appeared personally in battle.”

“Huns looked more imposing on horseback. Who doesn’t?”

“At one time the salaries of Russia’s foreign ambassadors were paid in rhubarb.”

That was the 86th edition of Get Wit Quick. Thanks for not 86ing it. Will Cuppy’s comic pessimism was the subject of GWQ No. 46. I realized about halfway through that you can footnote footnotes, but come on. My book Elements of Wit kicked up its footnotes and made itself at home. I’m low on rhubarb, so🦶 the ♥️ on your way out.

Robert MacFarlane describes footnotes in a literal way that i quite like in his book The old ways : « it is true that I remember the terrains over which I have walked barefoot differently, if not necessarily better, then those I have walked shod. I recalled them as textures, sensations, resistances, planes and slopes: The tactile details of a landscape that often pass unnoticed. They are durably imprinted memories, these footnotes, born on the skin of the walker meeting the skin of the land ».