Searching for the wittiest things ever written within the bounds of a single language is like looking for the world’s tallest tree in a single forest. And that’s why I’ve decided to switch this newsletter to Esperanto, efika tuj. Ču ne pli bone?1

But wait: Out of respect for the minuscule fraction of my readers who don’t speak the Universal Second Language, I’d have to translate that — and wouldn’t all the sparkle be lost in the process? Putting a pun through Google Translate is like putting a paper suit through the spin cycle, right?

Wrong, says Douglas Hofstadter.

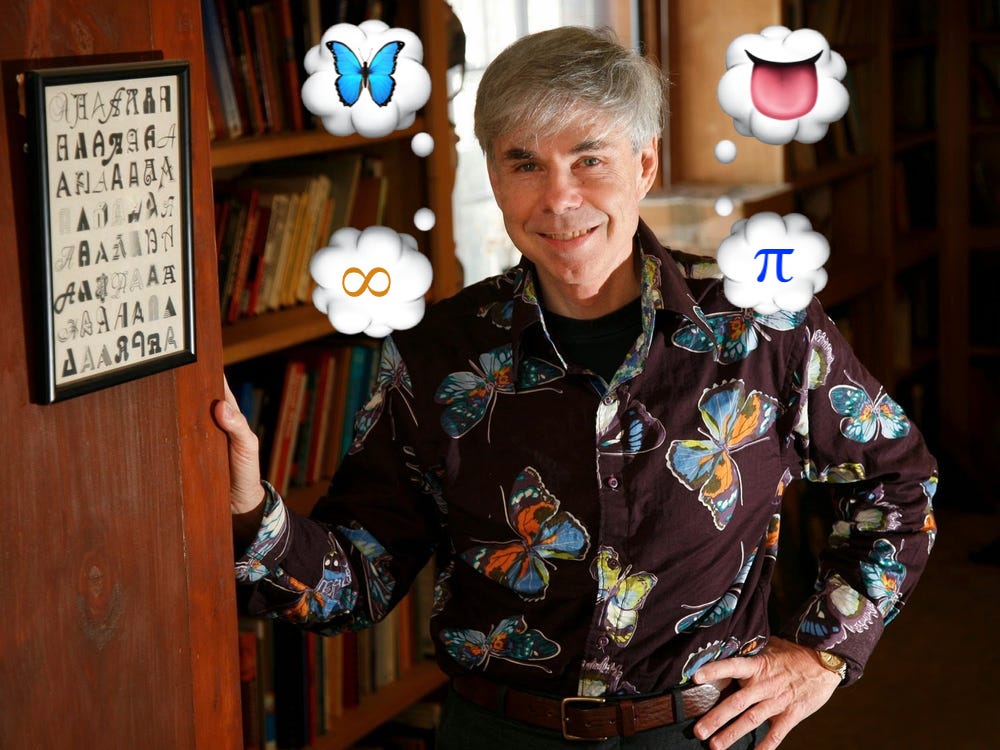

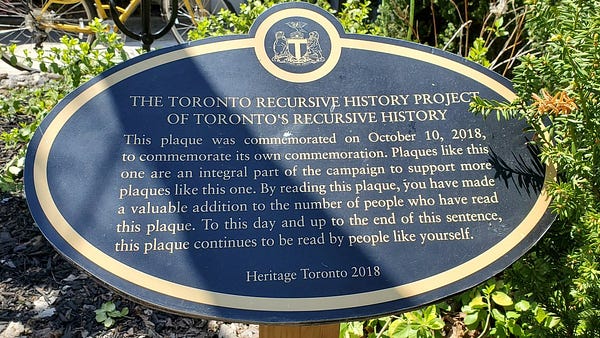

Hofstadter is a theoretical physicist, an AI skeptic, a proud Hoosier, a literary scholar, and a strange loop. (For proof, please see his 2007 book I Am A Strange Loop.) He also coined Hofstadter’s Law, which states that things always take longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.2 This self-referentiality in turn inspired this sign on my front lawn:

Hofstadter’s 1997 book Le Ton beau de Marot: In Praise of the Music of Language goes deep on how to think about translation. He set out to write “another sprawling book encompassing my many interests” — a laudable goal given that his first won the Pulitzer Prize — and here are two admirable vistas from within that enjoyable sprawl.

First, why do we give concert pianists top billing while literary translators aspire to invisibility? As he writes:

I would find it so enormously refreshing and touching if, just once in a while, some famous classical performer, right at the peak of all the frenzied applause, would unexpectedly whip out a photograph of the composer who created the work that actually transfixed the audience, would hold it up and say, “Thanks so much, my friends, but here’s the one you really should be thanking.”

In fact, he argues, a “skilled literary translator makes a far larger number of changes, and far more significant changes, than any virtuoso performer of classical music would ever dare to make.” For these second-order artists, “it’s totally humdrum stuff for new ideas to be interpolated, old ideas to be deleted, structures to be inverted, twisted around, and on and on.”

(To translate that into Canadian, Sheila Fischman should be at least as celebrated as Glenn Gould.)

And once you elevate the art of translation, Hofstadter argues, nothing need be lost into it. Every pun, every turn of phrase can be carried across the linguistic divide. Hofstadter describes himself as pilingual — he speaks English, French, and Italian, “with several other languages having small to tiny fractional values,” adding up to 3.1415… — and he thinks “there are hidden puns lying around at all times, and that even the wittiest of punsters miss 99 percent of them.”

Still, he jumps into the 1% by presenting excerpts from his personal collection of special, potentially untranslatable puns:

“A mistress is halfway between a mister and a mattress.”

“Parking is such street sorrow.”

Boids, “a documentary on artificial robot-birds, whose title draws on ‘android’, ‘humanoid,’ etc, while also doing a stereotyped Brooklyn accent on ‘birds’”

Still, he argues, “my general sense is that for nearly every pun in language X, there are one or more very close puns in language Y.” And then he recalls a book about primates and language that he spotted in the window of a Paris bookshop: Le signe et le singe.

The dull, obvious translation is The Sign and The Monkey, but he instantly flew into a reverie of possibilities: Monkeysigns! Simiotics! Apistemology! Of Simians and Symbols! Of Monkeys and Mots!

That book has yet to be translated, despite the fact that Douglas Hofstadter landed on the title Chimp A ’n’ Z’s. 🙊

Quick quips; fulmini3

“Whenever the literary German dives into a sentence, that is the last you are going to see of him till he emerges on the other side of the Atlantic with a verb in his mouth.”

— Mark Twain

“For more than forty years I have been speaking prose without knowing it.”

— Molière

“Non tutti, ma buona parte.”

— An Italian noblewoman’s reply when Napoleon exclaimed that all of her countrymen were scoundrels. “Not all, but a good part,” she told Bonaparte.

The 98th edition of Get Wit Quick was translated from a bunch of neural sparks into Google Docs and then pasted into Substack. I type in Georgia (the typeface, not the country) but note that Hofstadter is a Baskerville man through and through. He also admits that speaking π languages is a “a cute joke, but just between you and me, π is probably an overestimate. Maybe e would be closer — but don’t tell anyone!” His secret is safe down here in the fine print. You could fit pi copies of Elements of Wit: Mastering The Art of Being Interesting in one Ton beau de Marot, but why would you? Frappez le ❤️ en bas, if you please.

Isn’t that better? (It obviously isn’t.)

Which I did! And still this issue was three hours late.

Italian lightning, which is two parts Campari and one part gin, topped with prosecco. Prost! Echo?