One might think the basics of good manners would be acceptable to the Great Wits. After all, all major world religions and most of the non-religions agree on some version of the Golden Rule. But noooo:

“Do not do unto others as you would that they should do unto you. Their tastes may not be the same.”

— George Bernard Shaw

Shaw enjoyed being the hair in the soup of polite society, a metaphor that works because of his prodigious beard and the high fibre content of his work. He knew both what to say to get invited to the fancy parties and what to say to get kicked out of them. As an Irishman, like Swift and Wilde, he was at the ideal remove to both enjoy and critique English manners.

“Good breeding consists in concealing how much we think of ourselves and how little we think of other persons.”

— Mark Twain

In Sorry! The English and their Manners, Henry Hitchings says his countrymen and women are as polite as they are rude, a paradox that works because “extreme rudeness and elaborate politeness both stem from feelings of unease; they are different techniques for twisting one’s way out of discomfiture.”

“The readiness of the English to apologize for something they haven’t done is remarkable, and it is matched by an unwillingness to apologize for what they have done.”

— Henry Hitchings

There’s no better example of this polite rudeness than when Princess Margaret (noble birth, deeply insecure, heavy makeup) met Boy George (karma chameleon, newly famous, heavy makeup) in 1984.

“I don’t know who he is but he looks like an over-made-up tart,” she was overheard saying. (As opposed to an under-made-up tart.) Kensington Palace later denied the comment and no apology was offered. As Craig Brown recounts in his zippy biography of the Princess, Boy George happily talked to reporters about the incident:

“I don’t think I’m special but I do object to having been called a tart. It’s a damn cheek. I bring more money into this country than she does. Princess Margaret went to school for elocution and I come from the gutter, which just goes to show you can’t buy manners.”

— Boy George

Maybe the Americans are better at manners? If so, you’d have to credit Judith Martin, the newspaper columnist best known as Miss Manners. Her best quality is that it’s never entirely clear if she’s joking, which makes her very entertaining to read. When one of her Gentle Readers asked if there were “any guidelines that will help me feel correct in all occasions,” she responded with two tenets she had been told when she “was a mere slip of a girl” and that had “served her well in all the vicissitudes of life ever since”:

“1. Don’t

2. Be sure not to forget to”

— Judith Martin

Thanks?

But does anyone with the perspicacity to seek out a guide to manners actually need such a thing? Quentin Crisp’s Manners from Heaven assumes not, as it begins with the observation that “Nothing more rapidly inclines a person to go into a monastery than reading a book on etiquette.” His book advises you “neither how to eat an artichoke nor how to address an archbishop.” And while Miss Manners uses the words manners and etiquette interchangeably, Crisp is quite clear that etiquette is about exclusion, whereas manners are about inclusion:

“To drink from your fingerbowl may be a breach of etiquette, but if a host, seeing his guest make this mistake, did the same, it would be a sign of good manners.”

— Quentin Crisp

Manners maketh man, goes the old line quoted to decent effect in the otherwise bleak Kingsman movies. But of course the opposite is also true, and the basic reason we make manners is to reduce violence. There’s a reason that Margaret Visser’s The Rituals of Dinner, the definitive history of table manners, starts with an unexpectedly long and detailed description of cannibal societies. “Many were the methods of preparing a man as a meal,” Visser notes dryly.

“Eating is aggressive by nature, and the implements required for it could quickly become weapons; table manners are, most basically, a system of taboos designed to ensure that violence remains out of the question.”

— Margaret Visser“There was an Old Person of Buda

Whose conduct grew ruder and ruder;

Till at last, with a hammer,

They silenced his clamour,

By smashing that Person of Buda.”

— Edward Lear

As a flamboyant effeminate man in mid-century rural England, Crisp experienced more brutal violence than most in what he called the “hack-and-stab world.” His manners are the most hard-won, and earn him this last word:

“Manners do not grow in mountainous country. Manners are for the plains where no one is above or below us; and indeed, the well-mannered treat all people as their equals.”

— Quentin Crisp

Quote Vote

“It seldom pays to be rude. It never pays to be only half-rude”

— Norman Douglas

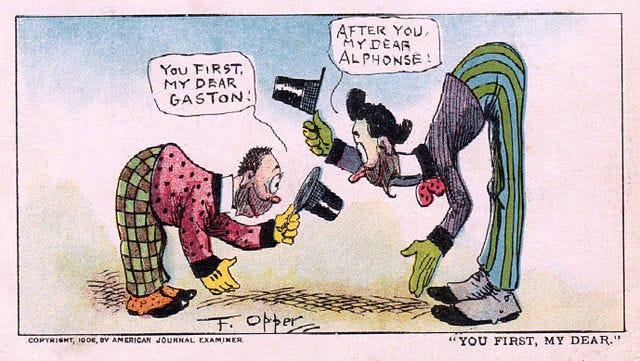

Here’s hoping we aren’t setting up an Alphonse and Gaston situation in this week’s Quote Vote, as we’ll need to make a choice. Don’t worry about the runners up! As the record of past votes shows, they live to run again!

Speaking of…

Forks

Crispness

Get Wit Quick No. 178 is a damn cheek. My book Elements of Wit: Mastering The Art of Being Interesting advised readers how to address an artichoke and eat an archbishop. If someone has tapped the ❤️ below, it’s good manners to tap it as well.

Thank you, Sir, for this lovely post.