Isn’t it convenient how the pandemic has reminded people that they were right all along? If this novel coronavirus has taught us anything, it’s that we all need to finally start speaking Esperanto. Everyone is dressing their hobby horses up for the big show.

Of these, vegetarianism is among the least tangential. From wet markets to meat-packing plants, there’s definitely a narrative thread to be pulled. Salad enthusiasts might look to George Bernard Shaw’s example of how to promote their diets — and then look right past him.

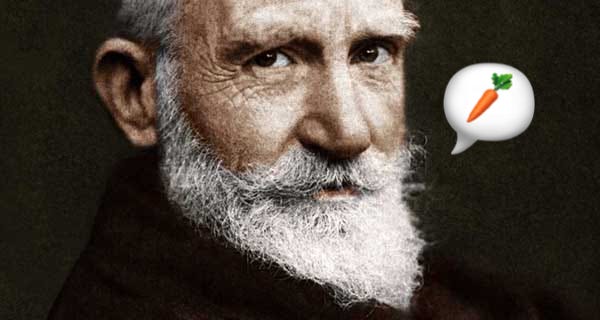

The playwright and polymath was, for a time, not just the most famous vegetarian on the planet but one of its most famous humans. Both Einstein and Churchill identified him the preeminent writer of his time. Until Bob Dylan joined him, he was the only winner of both a Nobel Prize and an Academy Award (a twofer hereafter called the Nobscar, considerably more exclusive than the EGOT).

As Terry Eagleton writes:

The tall, gaunt, puckish, red-bearded figure in a Jaeger woollen suit and knickerbockers was to become as much of a global icon as Mickey Mouse. He was the image of an Edwardian loony lefty. Vegetarianism was part of the package: ‘A mind the calibre of mine,’ he remarked, ‘cannot derive its nutriment from cows.’

Shaw gave up meat at the age of 25 and made this fact an essential part of his image. He was everywhere with an opinion on everything, and it was all powered by plants. His housekeeper published a cookbook of his favourite recipes after his death, writing in the foreword that “Having become a vegetarian, he kept thinking of fresh persuasive phrases to induce people to accept what had by now become his conviction.” Those phrases ranged from lines like:

“A man of my spiritual intensity does not eat corpses.”

To more elaborate and somewhat self-defeating arguments such as:

“My hearse will be followed not by mourning coaches but by herds of oxen, sheep, swine, flocks of poultry, and a small traveling aquarium of live fish, all wearing white scarves in honour of the man who perished rather than eat his fellow creatures.”

And yet, with vegetarianism as with socialism, Irish independence, human rights, and Shaw’s many other crusades, his fresh persuasive phrases never quite persuaded anyone. Why? In part because he talked about himself rather than his audience. And because, as the historian Egon Friedell put it:

He puts his moral purgative in the sweet-tasting cover of a peddled drama, a burlesque, or a moving piece, just a tamarind pastille is lodged in chocolate. Unfortunately the public is even slyer than Shaw. It licks off the good chocolate and leaves the tamarind.

Shaw was the phrase “too clever by half” come to life. That formula tells you exactly when a sharp wit becomes a thorn in your side: If 1.0 is a perfect cleverness score, then 1.5 describes someone who is so clever they turn in on themselves. On this scale — which itself scores a 1.2 — George Bernard Shaw oscillated between 1 and 2.

Ultimately GBS was a bad spokesman because he was too good a speaker: People wanted to hear him talk, but they didn’t listen to what he had to say.

Quick quips; lightning

“Shaw could turn the aphorism into a bugle for his propaganda,” Louis Kronenberger wrote. Some notable bugle blasts:

“It’s all the young can do for the old, to shock them and keep them up to date.”

“Life does not cease to be funny when people die any more than it ceases to be serious when people laugh.”

“You have learned something. That always feels at first as if you had lost something.”

“A man’s interest in the world is only the overflow from his interest in himself.”

That’s the 48th issue of Get Wit Quick, a weekly licking of chocolate from pastilles. Weird Al should have done a cover of Desperado called Esperanto. As I told Vice whilst promoting Elements of Wit: Mastering The Art of Being Interesting: “George Bernard Shaw was originally a terrible speaker and about as sharp as a beach pebble, yet over time he worked on it and developed into one of the great wits of his day.” Tapping the ♥️ below is the digital equivalent of draping a white scarf on a live fish.