The Wit’s Guide to Imperialism

Or, duck and cover

If you had one multiplujillion, nine obsquatumatillion, six hundred and twenty-three dollars and sixty-two cents, would you keep looking for more? The everyday actions of the richest men on earth suggest that you would. But what if you were a duck?

“If you can count your money, you don’t have a billion dollars.”

— J. Paul Getty

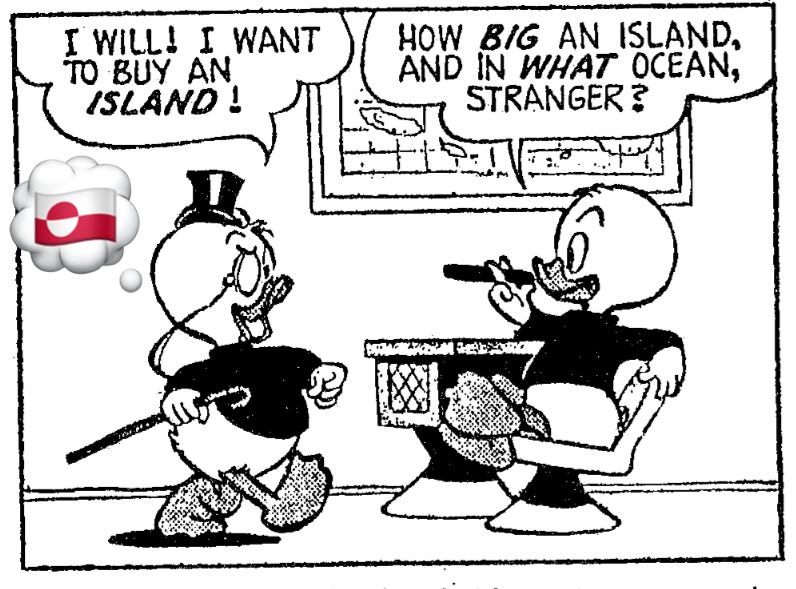

There’s no better guide to the recent history of cultural imperialism than Donald Duck. Together with his hyperfantasticatillionaire Uncle Scrooge and nephews Huey, Dewey and Louie, the white waterfowl undertook a long series of overseas adventures in comic books distributed throughout the world. This extended avian family waddled across the globe in search of treasures like Inca gold, Viking helmets, square eggs, and the lost crown of Genghis Khan. And yes, these comics directly inspired the creation of Indiana Jones.

“Behave like a duck — keep calm and serene on the surface but paddle like crazy underneath.”

— Unknown

In 1971, Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart published How To Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comics, a book-length Marxist tract explaining how the stories so popular in Dorfman’s native Chile were threaded through with Yankee propaganda. These ducks find a traditional culture, convince the primitive peoples to give up their most valuable resources, and generally leave things worse than when they found them. Would you believe that the ludicrously wealthy Scrooge McDuck puts his own face on the Sphinx and decides he belongs on Mount Duckmore?

“Adventure is nothing but a romantic name for trouble.”

— Louis L’Amour

Dorfman and Mattelart’s analysis even explains why there’s an Uncle Scrooge and nephew ducklings but no parents: “Since power in Disney is wielded not by a father, but by an uncle, it becomes arbitrary.” Unfortunately for Dorfman, thousands of Chilean Disney fans took umbrage at his sophisticated exegesis. As one historian wrote, “portly grandmothers tried to run him over with their cars, and one night his bungalow in Santiago was stoned by irate mobs of children and parents holding up placards and shouting, ‘Viva el Pato Donald!’’”

“The ridiculous empires break like biscuits.”

— Roy Fuller

And here’s the fun part: Dorfman misread Donald Duck. Sure, the Disney empire propagated American ideals of capitalism, consumerism, triplets, and gloved animals. But the specific comics he was critiquing were the work of Carl Barks, a gently subversive genius who toiled in underpaid obscurity for the House of Mouse. When the art historian David Kunzle was asked to write a foreword for Dorfman’s tract, he tried to explain that the authors misunderstood what Barks was trying to say. “I saw many of Barks’ best stories not as justifications of imperialist adventure,” Kunzle wrote, “but as satires upon it, in which the imperialist Duckburgers come off looking as foolish as — and far meaner than — the innocent Third World natives.”

“A great empire, like a great cake, is most easily diminished at the edges.”

— Benjamin Franklin

To the extent that Barks had a philosophy (as unpacked in this excellent paper titled “Ten Cent Ideology” by the historian Daniel Immerwahr), it was that everyone would be better off if they just stayed home. As he said in an interview, “I feel our civilization reached a peak about 1910. Since then we’ve been going downhill.” And the only reason Uncle Scrooge had such an imperialist itch is that he couldn’t stand the hometown he built from nothing. “I want to leave Duckburg with its smog and noise and shoving people,” he says, “even though I am the guy that started all of these smelly industries!” Marxism, meet Barksism.

“What fascinates and terrifies us about the Roman Empire is not that it finally went smash but that … it managed to last for four centuries without creativity, warmth or hope.”

— W.H. Auden

Eventually, even Dorfman came around. “Scrooge extracts wealth directly from mother nature, without hurting anybody, just by the sweat of his feathers,” he wrote in 1984. “Just like his namesake, Ebenezer, McDuck has, underneath a flint-skin exterior, a heart of gold truer than what lies in his safe-deposit boxes.” Dorfman even likened Barks to Lewis Carroll, writing that “he pushed back the boundaries of what was called reality and let his imagination go, grow, overflow.”

“Laughter is America’s most important export.”

— Walt Disney

There is a wonderful irony in the fact that the Donald Duck comic books were a global phenomenon, selling 250 million copies a year at their beak and bringing American culture across the globe — all with the implicit message that it would have been better to have left the globe alone. Or could it be that’s exactly why they were so popular? If it looks like a duck and walks like a duck, maybe it doesn’t need to wear pants.

“An Englishman does everything on principle: he fights you on patriotic principles; he robs you on business principles; he enslaves you on imperial principles.”

— George Bernard Shaw

I didn’t expect things to go in this direction, but then imperial adventures rarely go as planned! One great detail from Immerwahr: Uncle Scrooge once agreed “to pay his weight in diamonds to a maharajah but then inhales helium until he weighs ‘sixty pounds less than nothing,’ requiring the maharajah to pay him diamonds.” I gotta pull a stunt like that with my paid subscribers! And for next week?

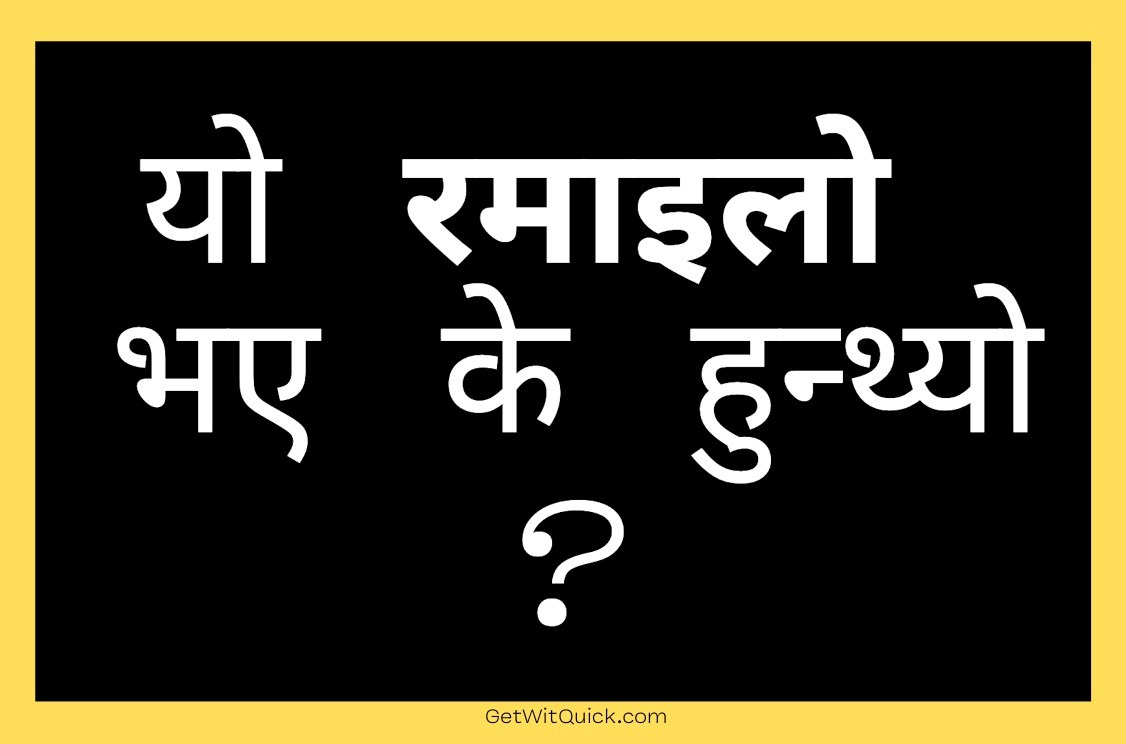

For all my penpals in Nepal…

Would you believe that I was asked to translate my stone-cold legendarily iconic “What If This Were Fun?” aphoristick sticker into Nepali? I was and I did! What sort of people read this newsletter, huh? According to my survey, “people like me, whose favorite part of any magazine was always the last page. Not because it was the last, but because it’s the one where fun and personality was allowed, no matter how serious the rest of the pages.” I love that! And if you also know who’s reading this, take 18 seconds to tell me in the The Inaugural Two-Minute Get Wit Quick Reader Survey!

I made Get Wit Quick No. 353 the same way Uncle Scrooge made his fortune, “by being tougher than the toughies, and smarter than the smarties! And I made it square!” Well, I cut a few corners. This newsletter’s mascot is a magpie named Magnus after the magician in Robertson Davies’ Deptford Trilogy. The title font is Vulf Sans, the official typeface of the band Vulfpeck. The book was Elements of Wit: Mastering The Art of Being Interesting. If you like your Duckbergers rare, peck the ❤️ below.

“Laughter is America’s greatest export” makes me think that laughter, is the most perfect euphemism for freedom. To be able to laugh, especially at corrupt trillionaires and their orange-ambition tour, is the duck feather in the proverbial cap of freedom! Great article, as always Ben! 💙

Fascinating how Barks embedded anti-imperialist critiques inside mass-market entertainment that literally exported American culture worldwide. The irony of Dorfman initially missing the satire while readers globally loved Uncle Scrooge precisely because he exposed greed's absurdity is pretty wild. Back when I was studying propaganda theory, this exact misread came up as a textbook case of how context collapse works diffrently in transnational media.