The Wit’s Guide to Ambiguity

Or, not unclear

The thing about ambiguity is, um, many things. It’s both a particle and a wave, which is why it’s always gesturing goodbye. There’s a famous work of literary criticism called The Seven Types of Ambiguity, and there’s also a novel by that name. It’s only fair that we swap the book jackets to see if anyone notices.

“I have always felt that a woman has a right to treat the subject of her age with ambiguity until, perhaps, she passes into the realm of over ninety. Then it is better she be candid with herself and with the world.”

— Helena Rubinstein

The first type is linguistic, a form perfected by Groucho Marx. He could squeeze an ambiguous prepositional phrase until it squeaked, with his two perfect examples being:

“I shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got in my pajamas, I’ll never know.”

“Outside of a dog, a book is a man’s best friend. Inside of a dog, it’s too dark to read.”

The second type is attributional, which explains why this gem is often erroneously credited to Marx:

“Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana.”

The third type is illegal, and it really only existed in the Soviet Union. In the 1930s, Stalin’s censors did their best to promote odnoznachnost, or one-meaningness. As the historian Jan Plamper writes, this meant newspaper editors had to monitor not only the content of their stories but also the layout. Censors “were expected to hold newspaper pages against the light to prevent undesirable juxtapositions from emerging. In a 1937 issue of Trud, one page showed a portrait of Stalin, while the backside showed a worker swinging a hammer. When held against the light, the worker seems to be hitting Stalin on the head with the hammer.” If that seemed too subtle, the gulag wouldn’t be.

“Ambiguity, the devil’s volleyball.”

— Emo Phillips

The fourth type is diplomatic, better known as creative or constructive ambiguity. It means that any number of parties can agree on anything if you make it fuzzy enough. We can’t have Taiwan in the Olympics? No problem, we’ll call it Chinese Taipei! In practice, this often means you let each warring party think they’re getting what they want in the peace treaty, then hand it over to someone else to hash out while you’re accepting your Nobel Prize. This was one of Henry Kissinger’s great contributions to the art of diplomacy.

“The greater the ambiguity, the greater the pleasure.”

— Milan Kundera

The fifth type is artistic, and this one is the clincher. Why? Because it’s a shortcut to memorability. David Lynch admitted as much when he was promoting Twin Peaks, his 1990 foray into network television. When a Los Angeles Times reporter asked him if each episode would provide viewers with a sense of closure, he recoiled. No! Because “as soon as a show has a sense of closure, it gives you an excuse to forget you’ve seen the damn thing.”

“A smile is the chosen vehicle of all ambiguities.”

— Herman Melville

The sixth type is ethnocultural, aptly illustrated by

in his forgivably titled 1994 memoir Roots Schmoots: Journeys Among Jews. “The worst we suffered were sensations of ambiguity,” he writes of his Jewish upbringing in post-war Manchester. “We were and we weren’t. We were getting somewhere and we weren’t. … If we had any identity at all, that was it: we countermanded ourselves, we faced in opposite directions, we were our own antithesis.”“The awareness of the ambiguity of one’s highest achievements (as well as one’s deepest failures) is a definite symptom of maturity.”

— Paul Tillich

And the seventh type is where I admit that the previous six aren’t actually from William Empson’s book of literary criticism. But then, I never said they were. Note that a cleverly ambiguous turn of phrase presents two options and then affirms both. Was this newsletter a breezy read or an insightful analysis? Yes!

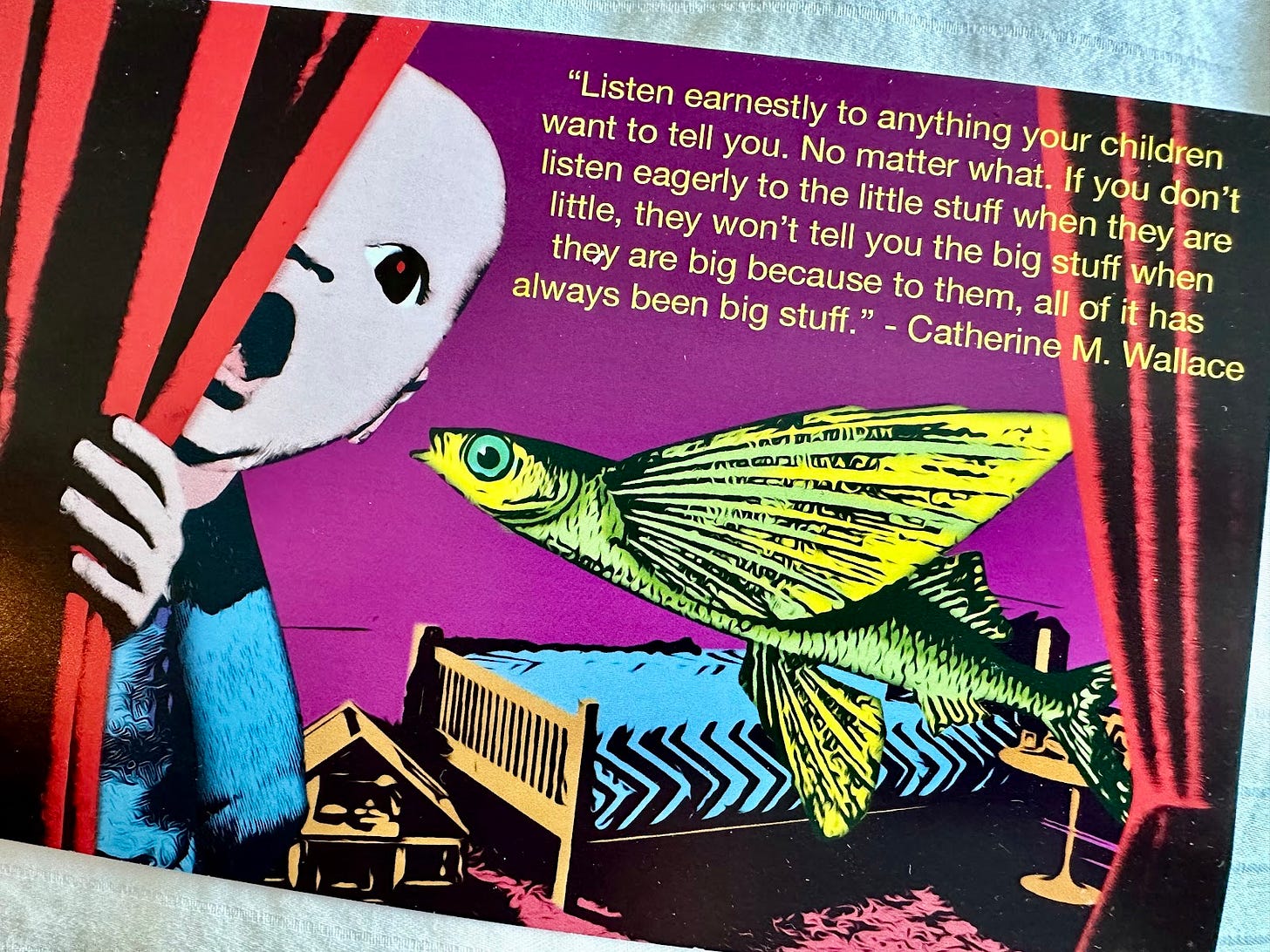

Each month, I commission a new illustrator to create a postcard with the quip of their choice to send to my lovely paying subscribers. I always offer up a selection of lines but encourage the artist to BYOB, where the last B stands for “bon mot” and the first B stands for “bring.” Happily, Montreal illustrator Pierre-Paul Pariseau came to play with this line:

“Listen earnestly to anything your children want to tell you. No matter what. If you don’t listen eagerly to the little stuff when they are little, they won’t tell you the big stuff when they are big because to them, all of it has always been big stuff.”

— Catherine M. Wallace

And naturally, M. Pariseau chose to interpret that thought with a flying fish:

To have this fish flown into your mailbox later this month, upgrade your subscription today!

“Neurosis is the inability to tolerate ambiguity.”

— Sigmund Freud

I refuse to tolerate an ambiguous subject for next week’s newsletter. Please, deliver the prognosis for my neurosis:

That was and wasn’t but mostly was Issue No. 288 of Get Wit Quick, your unambiguously weekly inbox filler. The mascot is Magnus the Magpie, an intelligent bird who collects shiny things named after the magician from Robertson Davies’ Deptford Trilogy. The title font is Vulf Sans, the official typeface of the band Vulfpeck that will have you wondering, “Is subtle funk even funkier?” The current temperature is -10C. The book was Elements of Wit: Mastering The Art of Being Interesting. And the ❤️ may be tapped, or not.

dear benjamin,

wonderful quotes as always!

i particularly love this one:

“Listen earnestly to anything your children want to tell you. No matter what. If you don’t listen eagerly to the little stuff when they are little, they won’t tell you the big stuff when they are big because to them, all of it has always been big stuff.”

— Catherine M. Wallace

it's so good!

thank you for sharing!

love

myq

I found this post particularly satisfying. My father spent his waning years of increased memory loss and dementia (unfortunately--or maybe fortunately--depending on how you look at it) railing against the growing conservatism in politics and religion, blaming this trend on the inability to tolerate ambiguity among the right-wing.