Deliver Us From Nowhere

Canada Post’s move to community mailboxes is an opportunity to design infrastructure with a sense of place. Surely, Canada can do better than our current ‘failboxes’

The Globe and Mail, December 13, 2025

Life is abundant and at the best times personally satisfying, but it is lived in a world designed for efficiency and little else,” the journalist Robert Fulford wrote in the preface to A Life in Paragraphs, his final book. “Monotony, blandness, drabness: this is what we build for ourselves and what we are apparently fated to go on building.”

Few things better embody that default to dreariness than Canada Post’s community mailboxes. These dull postal dumpsters are already how most Canadians get what’s left of their analogue bills, magazines, junk mail and, at this time of year, Christmas cards. As the Crown corporation continues to lose more than $10 million a day, the federal government is finally allowing the end of home delivery for the four million addresses that still enjoy it.

The last time Canada Post tried this, in 2013, Canadians revolted. There were thousands of formal complaints, multiple court challenges, and one especially photogenic protest: the mayor of Montreal attacking a community mailbox’s concrete foundation with a jackhammer. The discontent became an election issue. Justin Trudeau’s Liberals pledged to “stop Stephen Harper’s plan to end door-to-door mail delivery in Canada.” Once in power, they clarified that those who’d already lost home delivery wouldn’t get it back, locking us into the current hybrid hodgepodge of doors and boxes.

Now the shift is inevitable. Amazon’s same-day parcel delivery has gutted Canada Post’s most lucrative line of business, and there’s less and less letter mail to carry. Switching us all over to community boxes will save $400 million a year, the government estimates.

But just because we need centralized postal depots doesn’t mean we need these failboxes. This is an opportunity to do something exciting: a nation-building project at the neighbourhood level.

Here, then, are some ideas. Some would be cost-competitive with what’s out there now; others are wildly impractical; none are fully resolved. Every one of them could easily be smothered by a well-meaning committee. The original designer of the current mailboxes has said as much. Writing in these pages in 2015 about his time at Canada Post, Ross J. Slade recalled that “design thwarted by terrible execution would be an ongoing theme.”

So let us dare to dream – or at least politely ask for something better.

This, after all, is the moment in Canada’s history when we’re supposed to build things we never imagined at a pace we never thought possible. Can we at least prototype the ideas below at a reasonable pace?

We aren’t fated to monotony, blandness, and drabness, not if we demand that Canada Post deliver something better.

I. Make them less ugly

Let’s start from the premise that a mailbox shouldn’t be depressing. Good design can add value by making everyday infrastructure pleasant, coherent and worth looking at. Beauty can be treated as a civic duty, a differentiator for our national brand.

That’s why we began by reconsidering the visual language we use to represent Canada. Our national design shorthand of maple leaves, plaid, and canoes may be nostalgic, but Tim Hortons has cornered that market.

Since these boxes are additions to the landscape, why not take inspiration from what’s already there?

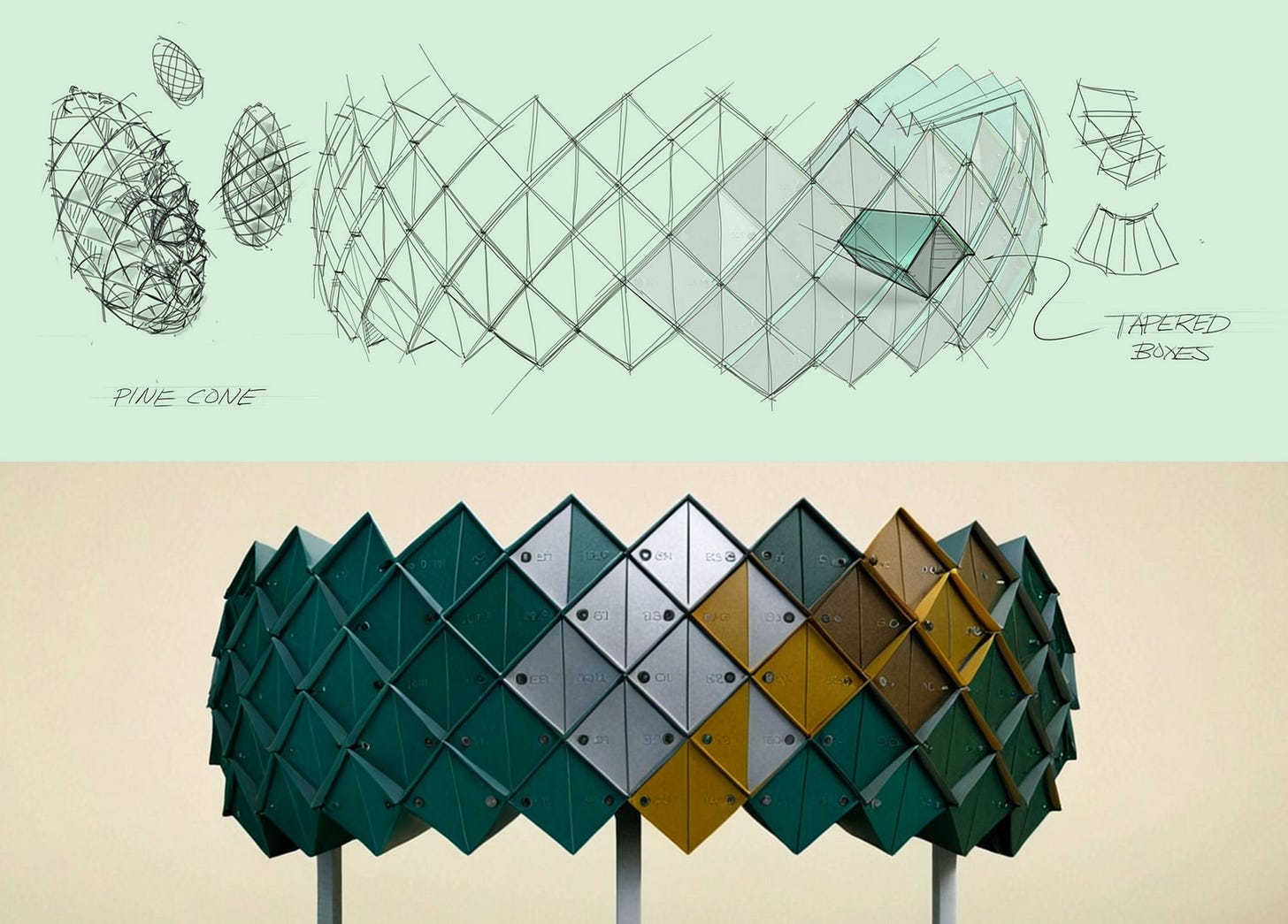

We started with the pine cone – or, more broadly, the cones of coniferous trees. Conifers cover much more of our country than the maple, pushing further north. Their scales protect the seeds and open to release them. That led us to the doors of our mailbox: spiralling tiles that hold your mail, echoing the pattern of a cone.

These “mail cones” could be built with the same high-grade aluminum and concrete used in today’s community mailboxes.

They would have the same functional features Canadians expect: sturdy construction, parcel compartments and an outgoing mail slot. They’d just do it with a touch of imagination and an awareness of place.

II. Make them more useful

Once beauty grabs attention, the next step is intentional engagement. How do we make these places you actually look forward to visiting? Or, put another way: what should every Canadian be able to find within a short walk of their front door? Community mailboxes are one answer to that question, but there are many more.

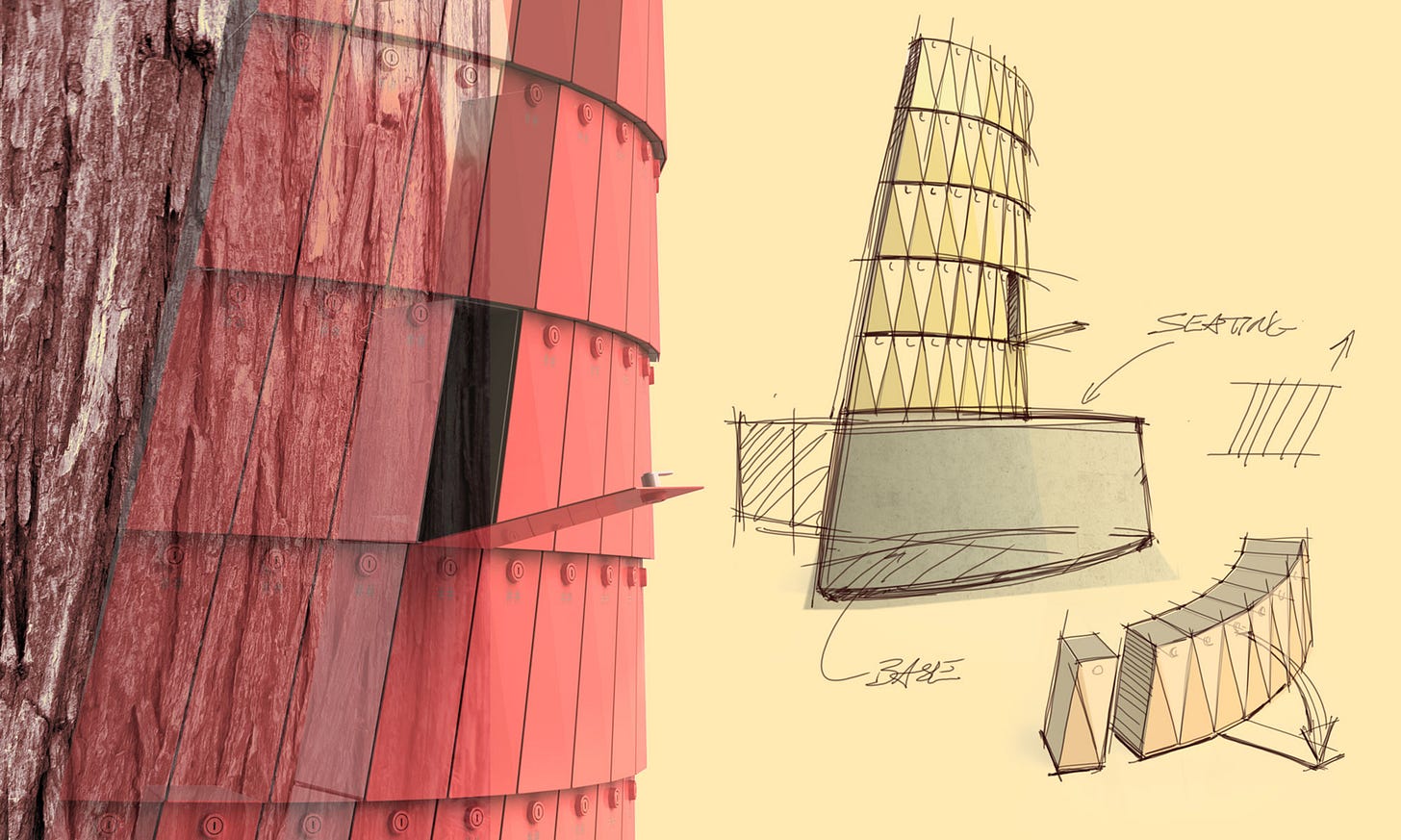

Here, we took inspiration from the bark of the eastern red cedar to suggest a mailbox that includes seating, shade, and a small moment of pause. Less of an errand, more of an experience.

From there, we might incorporate the interesting things that already pop up organically on our streets: little free libraries, recycling drop-offs, bulletin boards, community food pantries for non-perishable items.

Then we can expand to more ambitious community endeavours: lending libraries for tools, seeds, and camping equipment, the latter bundled with entry passes to the nearest national park.

Each of these ideas would need management and oversight, but we can start by offering space and basic infrastructure – perhaps nothing more than modular lockers – and then learn from the volunteers and community organizations that step forward. For inspiration and expertise, look to The Thingery, the community-supported lending library that Chris Diplock has been building in Vancouver since 2011. And in the case of a seed library, let a thousand native Canadian flowers bloom.

Back in 2013, Canada Post’s then-CEO Deepak Chopra made a fool of himself by telling a parliamentary committee that seniors had actually been asking him for a way to get more exercise and fresh air. As it happened, he had just the solution. Imagine if that were an actual selling point instead of an impromptu talking point.

Seven Canadian cities have bike-sharing programs; adding a community mailbox equipped with bike pumps and tools next to a docking station would make each site a hub for cyclists.

The same goes for basic outdoor fitness equipment: bars for push-ups, pull-ups and dips. To add an aerobic component, provide a small map with distances to neighbouring boxes. You’ve got the Mail Run. Connect them across the country and you’ve twinned the Trans Canada Trail.

III. Make them make place

The trendy term “placemaking” is a clever way to rally people around what ought to be common sense. A guide published earlier this year by Canada’s Placemaking Community describes it as the practice of transforming public space into a vibrant, accessible place that enhances quality of life, social cohesion, economic value and cultural health. Across the country, this looks like everything from the Shawnee Evergreen Community Association in Calgary buying Muskoka chairs for public places to the plazaPOPS initiative to turn underused Scarborough parking lots into community gathering spots.

And what is mail about, if not place? You need to write the co-ordinates of a specific location on the front of your letter before you drop it in a box. The uniqueness of the destination is right there in the postal code.

So let’s make mailboxes about where they are. Start with a simple template for a historical plaque that highlights the natural, Indigenous and cultural significance of each site, a project tailor-made for local historians. Include a spot for a time capsule in each concrete base, one that could naturally include a sample of the day’s mail. Above all, make them about the communities that use them.

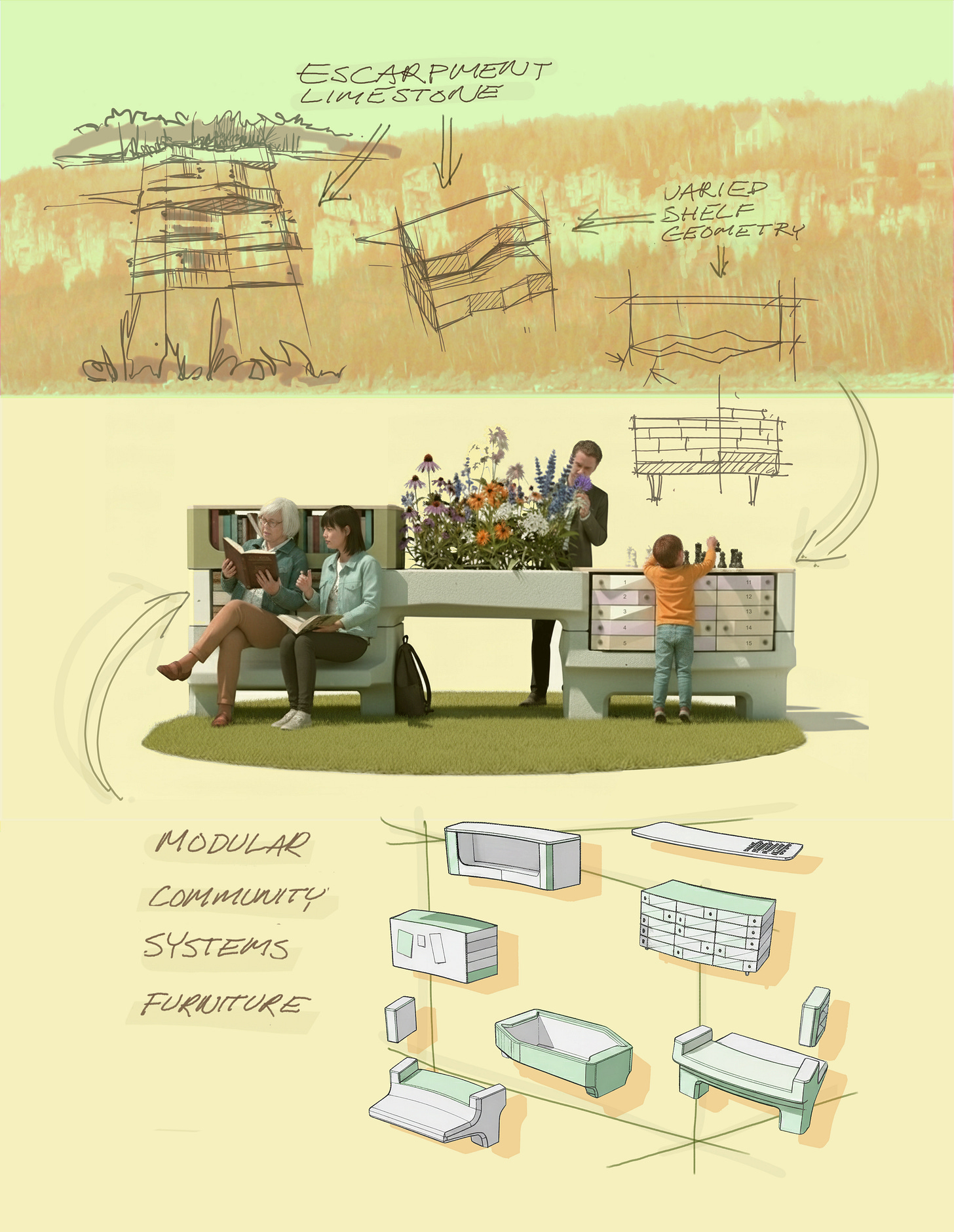

In this prototype, we’ve gone bigger, taking visual inspiration from the Niagara Escarpment to support the everyday activities of a flourishing neighbourhood: reading, lending, sharing, eating, drinking, planting and learning. Because each community is unique while community mailboxes must be somewhat uniform, we propose a modular design system, like a giant Lego set (or, since we’re Canadian, Mega Bloks).

IV. Make them have fun

In our digital age, the postal system can seem grossly inefficient. If we’re going to hold onto it, why not play into its impracticality? Why not play?

We want to see these structures adapted for community puppet shows. We want a national competition to find the country’s most visited mailbox. We want automat-style vending machines selling everything from stationery kits to umbrellas. We want a sister-city-style pairing of different community mailboxes, with a pen pal program. We want unused mailboxes turned into birdhouses, and we want Canada’s biologists to bring back the passenger pigeon as a viable means of delivery.

In winter, when you go to pick up your mail, you’ll likely remove your gloves to unlock the box. There’s a non-trivial chance you’ll drop one. A zero-cost addition to each mail depot could be an unlocked mailbox designated as the lost and found. With simple signage – “When you find a mitt on the ground nearby, drop it in here” – Canada could realize the long-held dream of a National Mitten Registry.

Since 1982, Canada Post has operated the very successful Letters to Santa program, through which children from around the world get a response from the North Pole when they send a letter with the H0H 0H0 postal code. This campaign strengthens our Arctic sovereignty, teaches kids the value of penmanship and generates more than a million pieces of letter mail each year. A special mail slot for Old St. Nick on every community mailbox could double that number, especially for Christmas in July.

And why should only one imaginary friend get mail? Let’s encourage letters to the Easter Bunny and the Tooth Fairy, and then keep going with Bigfoot and the other sasquatches and yetis that populate our dense hinterlands. The only way to know if Canada’s children have questions for Ogopogo, the lake monster of the Okanagan, is to ask them.

Speaking of Santa, why not a nationwide game of Secret Santa? With 41 million participants, you’ll never guess who left those festive socks in your mailbox.

And for the grinches who don’t want to talk to their neighbours, how about a premium service that alerts them when no one else is at the mailbox? Alternatively, we can force people to be more social by making their mail keys work like those on a nuclear submarine, requiring a designated neighbour to open their box at the exact same time. Sending someone a letter by mail in 2025 is somewhat ridiculous. Together, we can make it completely ridiculous.

Okay, back to reality. In the time it’s taken you to read this article, Canada Post has lost another $150,000. (If you paused to refill your coffee, that’s another $35,000 – hope it was worth it!) In this economy, we probably shouldn’t enlist members of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers to breed passenger pigeons. William Kaplan, the mediator whose report is driving the government’s actions, dismissed union ideas such as “introducing postal banking, seniors check-ins, establishing artisanal markets at postal stations, and transforming postal stations into community social hubs” as unrealistic. Focus on delivering the mail, he said. He didn’t insist it be delivered into bland, boring, unimaginative community mailboxes.

To quote Prime Minister Mark Carney’s speech to the House of Commons after passing the One Canadian Economy bill in June: “For too long, when federal agencies have examined a new project, their immediate question has been ‘why?’ With this bill, we will instead ask ourselves ‘how?’” So let’s not ask why we should bother fixing these eyesores, but instead how we can make them better.

The reason we hate community mailboxes is that they’re about loss. We’re losing convenience, service and tradition – if we haven’t already lost them. But we’re also getting something, something that could be good. We don’t have to accept a narrative of decline and austerity. With the same materials at the same cost, plus some clever design thinking, we could have the less ugly, more useful community mailboxes we actually deserve. We can give ourselves more than Canada Post can ever take away.