Edith Sitwell was an English poet of the early 20th century, part of a famous family, and a revolving door of quippery. She described herself as an “unpopular electric eel in a pool of catfish”; she had Marfan syndrome; she wrote several bestselling books of Elizabethan history; and her father installed a sign at their estate that proclaimed “I must ask anyone entering the house never to contradict me in any way, as it interferes with the functioning of the gastric juices and prevents my sleeping at night.”

The second line of her unfortunate Wikipedia page reads: “She reacted badly to her eccentric, unloving parents and lived much of her life with her governess.” (Having died in 1964, she never had to read her unfortunate Wikipedia page.) She’s also a reminder that every era is a noisy, complicated mess of cliques, conversations, and confrontations that eventually gets flattened out by historians on steamrollers. In the process, we lose the dimensionality of a character who was as critical of others as she was sensitive, the sort of English eccentric who wrote the book on English Eccentrics.

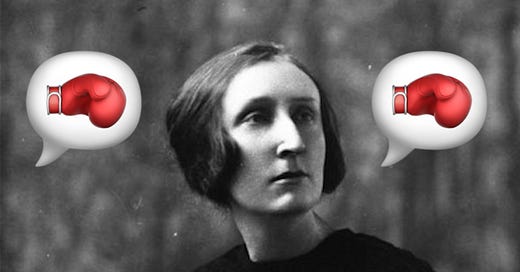

Happily, Edith Sitwell distinguished herself with a series of acid observations about her contemporaries:

“I do not want Miss Mannin’s feelings to be hurt by the fact that I have never heard of her. At the moment I am debarred from the pleasures of putting her in her place by the fact she has not got one.” — On Ethel Mannin

“I enjoyed talking to her but thought nothing of her writing. I considered her a beautiful little knitter.” — On Virginia Woolf

“Mr Lawrence looked like a plaster gnome on a stone toadstool in some suburban garden. ...He looked as if he had just returned from spending an uncomfortable night in a very dark cave.” — On D.H. Lawrence

“It is sad to see Milton’s great lines bobbing up and down in the sandy desert of Dr. Leavis’s mind with the grace of a fleet of weary camels.” — On F.R. Leavis

To which her contemporaries said, “Right back at ya, Edith” as follows:

“Then Edith Sitwell appeared, her nose longer than an anteater’s, and read some of her absurd stuff.” — Lytton Strachey

“I am fairly unrepentant about her poetry. I really think that three quarters of it is gibberish. However, I must crush down these thoughts, otherwise the dove of peace will shit on me.” — Noël Coward

“So you’ve been reviewing Edith Sitwell’s last piece of virgin dung, have you? Isn’t she a poisonous thing of a woman, lying, concealing, flipping, plagiarizing, misquoting, and being as clever a crooked literary publicist as ever.” — Dylan Thomas

“I have often wished I had time to cultivate modesty … But I am too busy thinking about myself.” — Edith Sitwell, piling on.

Dame Edith’s attitude toward such criticism was perfect: “All the Pipsqueakery are after me in full squeak,” she said, a line that fits nicely alongside Margaret Atwood’s “Nolite te Bastardes Carborundorum.”

When insulted, the best course is generally to smile and turn the other cheek. But if Edith Sitwell had done that, she’d be much less memorable. Sometimes, you just have to roll up your sleeves and fight back.

Quick quips; lightning

“He hasn’t an enemy in the world, and none of his friends like him.”

— Oscar Wilde

Saint Oscar (1854-1900) on his frenemy George Bernard Shaw and the perils of standing in the middle of the road.

“Anger makes dull men witty, but it keeps them poor.” — Francis Bacon

In which the English philosopher (1561-1626) describes a subject of Elizabeth I who forgets what side his bread is buttered and becomes crusty toward his queen.

“Calumnies are best answered with silence.” — Ben Jonson

The advice of the English dramatist (1573-1637) is good for personal preservation but bad for long-term quotability.

This concludes the 21st issue of Get Wit Quick, a uniquely weekly pipsqueakery. Is there such a thing as a popular electric eel? Less than a quarter of my book Elements of Wit: Mastering The Art of Being Interesting was gibberish. Your gastric juices will function more freely after tapping the ❤️below.