For the last hundred years, Edward Colston’s statue has stood in the middle of the city of Bristol. For the last four days, Edward Colston’s statue has sat at the bottom of the harbour of Bristol.

Colston, as many of us learned this week, ran the Royal Africa Company and was responsible for the enslavement of 80,000 Africans and the deaths of at least 20,000 more. There have long been calls to remove his bronze likeness from the city his wealth helped build, and this week those calls became action.

“It is a piece of historical poetry,” Marvin Rees, the mayor of Bristol remarked, “where a man who undoubtedly had slaves thrown off his ships during the passage at some point ended up under water, just like the bodies of enslaved Africans.”

Rees spoke perfectly to the current moment. There are rules, there are reasons to break rules, and there is value in taking the long view of why we have those rules. Colston’s statue was erected to keep his memory alive; his recent plunge made him a trending topic: Mission accomplished!

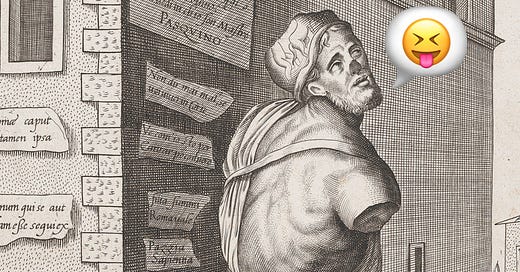

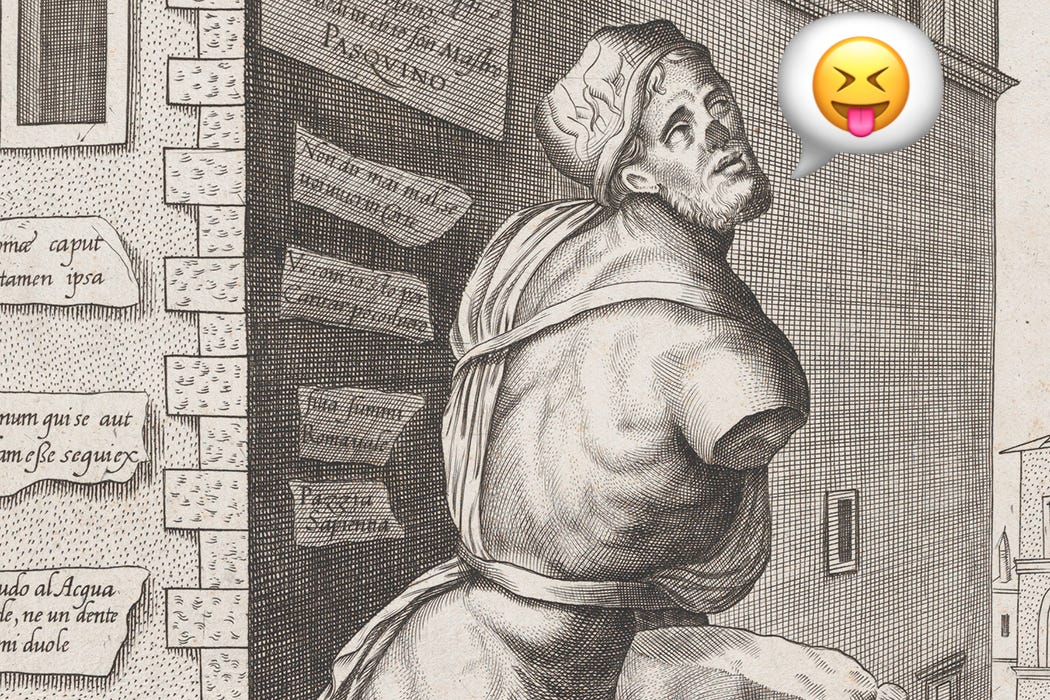

Statues and dissent have a long and intertwined history, and happily some of it is quite witty. A pasquinade is an anonymous work of barbed satire named for Pasquino, an armless Roman statue. This ancient fragment of a larger marble tribute to the gods was unearthed during construction in 1501 and stashed in a piazza; it is claimed that the statue earned its new name when Pasquino, a local tailor with some juicy Vatican gossip, scrawled what he knew on the monument.

Soon, all of Rome with something impolitic to say said it on Pasquino. The tradition spread to nearby sculptures — in that town, there’s always a nearby sculpture — and soon the assemblage became the Talking Statues of Rome, more formally known as the Congresso degli Arguti, or Congregation of Wits. They’d point out all the times the infallible fell, and all the excesses that everyone saw but no one could publicly acknowledge. As one pasquinade asked of a corrupt pontiff,

Great sums were formerly given to poets for singing. How much will you pay, O Paul, to silence me?

Today, Pasquino is the only member of the Congregation of Wits who remains in Rome and pasquinades must be affixed to a board next to him. He’s in decent shape for a 2,300-year-old and did his part to ridicule Silvio Berlusconi, though he hasn’t tweeted since 2006.

Unlike the statue of Edward Colston, Pasquino narrowly avoided his dip in the local waters. In 1523, Pope Adrian VI threatened to hurl the statue into the Tiber after one too many anonymous attacks on his papacy. The Holy Father thought better of it after being warned that “all the frogs of the river, becoming infected with his spirit, would adopt his style of speech and croak only pasquinades.”

Pasquino is a good reminder that the statue is not the person; in his case, he isn’t even a likeness of the gossipy tailor, or even a human. If a carved piece of stone can do some good in the world, huzzah to that. The silence of Bristol’s frogs speaks for itself.

Quick quips; lightning

“I would much rather have men ask why there is no statue of me than why there is one.” — Cato the Elder, who we remember not just for his great-grandson Cato the Younger.

“You have to accept the fact that sometimes you are the pigeon, and sometimes you are the statue.”

— Claude Chabrol, the New Wave filmmaker who understood that you can’t please everyone.

“I just chipped away everything that didn’t look like David.”

— Michelangelo describing his sculpting technique (but not really)

That’s the 50th issue of Get Wit Quick, which seems like a lot, no? The line that comes after “Plinth U been gone” is of course “I can breathe for the first time”. Before Colston’s statue was dumped, it was yarn bombed. You can’t call the writers of pasquinades vandals because Rome has some history with actual Vandals, and they weren’t nearly as clever. Elements of Wit: Mastering The Art of Being Interesting was my nonymous scrawl. Tap the ♥️ below and I promise the Pope will never find out it was you.