Malcolm X marks the thought

Or, how wit and humour do opposite things

We didn’t land on Plymouth Rock, Malcolm X told his audiences. Plymouth Rock landed on us.

It’s a great example of reverse-order repetition, or antimetabole. A more famous antimetabole came from another American leader in the 1960s: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” Malcolm X expresses the reverse sentiment of JFK, making his phrase a kind of meta-antimetabole, or maybe just a bole.

The man born Malcolm Little was a verbal bomb thrower, a master orator, and an eighth-grade dropout who “didn’t know a verb from a house” until he took correspondence courses in prison. When he learned how to debate, he described turning his mental fireworks into verbal fire in his posthumously published Autobiography of Malcolm X:

Standing up there, the faces looking up at me, things in my head coming out of my mouth, while my brain searched for the next best thing to follow what I was saying, and if I could sway them to my side by handling it right, then I had won the debate — once my feet got wet, I was gone on debating.

His 1964 Message to the Grassroots speech gives new meaning to the term “flat white” with one of the best coffee metaphors ever poured:

It’s just like when you’ve got some coffee that’s too black, which means it’s too strong. What you do? You integrate it with cream; you make it weak. If you pour too much cream in, you won’t even know you ever had coffee. It used to be hot, it becomes cool. It used to be strong, it becomes weak. It used to wake you up, now it’ll put you to sleep. This is what they did with the march on Washington.

To do battle by any means necessary sometimes meant going into the whitest places imaginable — the Oxford Debating Union, for instance — with a disarming smile, a sharp tongue, and a winning wit. There, he won the crowd just as soon as his opponent asked about his name:

He’s right, X is not my real name. But if you study history, you’ll find why no Black man in the Western Hemisphere knows his real name. Some of his ancestors kidnapped our ancestors from Africa and took us into the Western Hemisphere and sold us there, and our names were stripped from us and so today we don’t know who we really are. I’m one of those who admit it, and so I just put X up there to keep from wearing his name. (Hear it at 1:14:30 here)

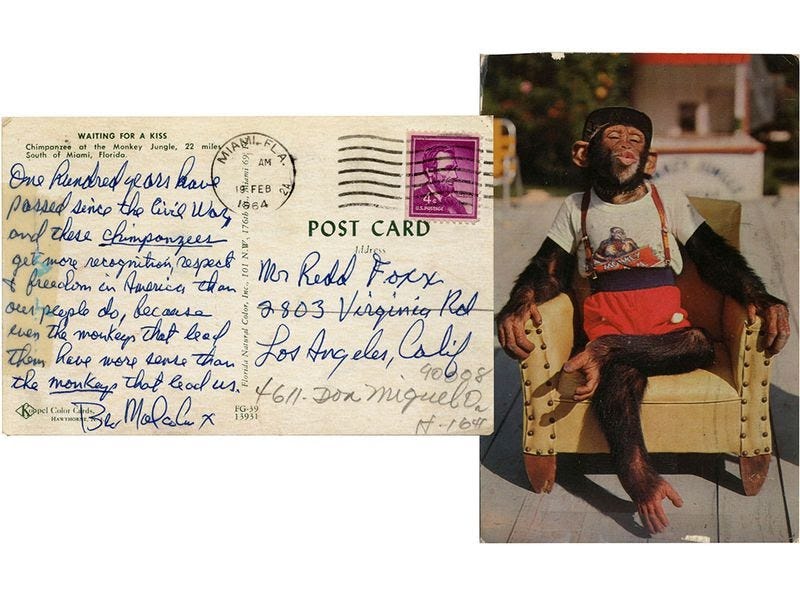

Malcolm X was often witty but rarely funny, and for good reason. Laughter defuses a situation; he wanted to light the fuse. He had something big to say and never missed an opportunity to say it. Take this jokey postcard he sent to his good friend Redd Foxx (the star of Get Wit Quick No. 14) in 1964:

Malcolm X was there to tell black audiences it was time to get out and white audiences not to get in the way. His wit was a tool to do that job. So when a black listener argued that he was an American because he was born in the United States, Malcolm X responded: “Now, brother, if a cat has kittens in the oven, does that make them biscuits?”

Quick quips; lightning

I waited at the counter of a white restaurant for eleven years. When they finally integrated, they didn't have what I wanted.

— Dick Gregory

Perhaps, after all, America never has been discovered. I myself would say that it had merely been detected.

— Oscar Wilde

Humor is laughing at what you haven't got when you ought to have it.

— Langston Hughes

So, that makes 32 issues of Get Wit Quick. The top photo is from Malcolm X’s appearance as the surprise guest on CBC’s Front Page Challenge, which actually may trump the Oxford Union as the whitest place imaginable. My book Elements of Wit: Mastering The Art of Being Interesting was published prehumously. Tap the ❤️below to feed kittens biscuits.