Oscar Wilde stood out from his contemporaries like a green carnation on a purple lapel. Which is why the most interesting part of his life was when he was just another aspiring poet jockeying for attention.

In the huge new biography by Matthew Sturgis, the epic portions of Wilde’s life are documented with newly uncovered material: The heights of his fame, the ill-advised court case, the years in prison, the coda on the continent. But of particular interest is how he became famous before he did anything of note.

How did he rise to the top? Sheer genius is what he wanted people to think, but the truth is a much better story. From his late teens to his mid 30s, he tried one self-promoting scheme after another to varying degrees of success. It was only at the age of 35, when The Picture of Dorian Grey was published in Lippincott’s magazine, that he really lived up to his self-declared genius.

When Wilde was 22, he quipped to friends that his idea of happiness was “absolute power over men’s minds, even if accompanied by chronic toothache,” while his definition of misery would be “living a poor and respectable life in an obscure village.”

To achieve the former and avoid the latter, he deployed this series of clever strategies to become famous:

1. Cultural chaperone

After he graduated Oxford and came to London, Young Oscar “failed to establish himself as a newspaper art critic, a tenured academic, a successful writer, or a traveling tutor.” The most marketable skill he had was his ready opinion, and so “he became a sort of cultural chaperone, a self-elected arbiter of taste, squiring fashionable women around art galleries and exhibitions.”

There was nothing wrong with the pictures hanging at the Royal Academy, he told one such lady, “except they are not paintings, and are not art at all.” Snap!

2. Hype man for professional beauties

Wilde made a practice of identifying the leading ladies of the day and writing sonnets in their honour, thus establishing “himself as the laureate of female loveliness, securing a ready readership and catching the reflected glow of his subjects’ glamour.”

His motives weren’t exactly hidden. “With your money and my brain we could have gone so far,” he said to one beauty, and to another “we will rule the world — you and I — you with your looks and I with my wits.” Yes, he said that to all the girls.

The actress Helena Modjeska saw his game. “What has he done, this young man, that one meets him everywhere?... He has written nothing, he does not sing or paint or act—he does nothing but talk. I do not understand.”

3. Self-nominated stereotype

His cleverest move was to become Jellaby Postlethwaite.

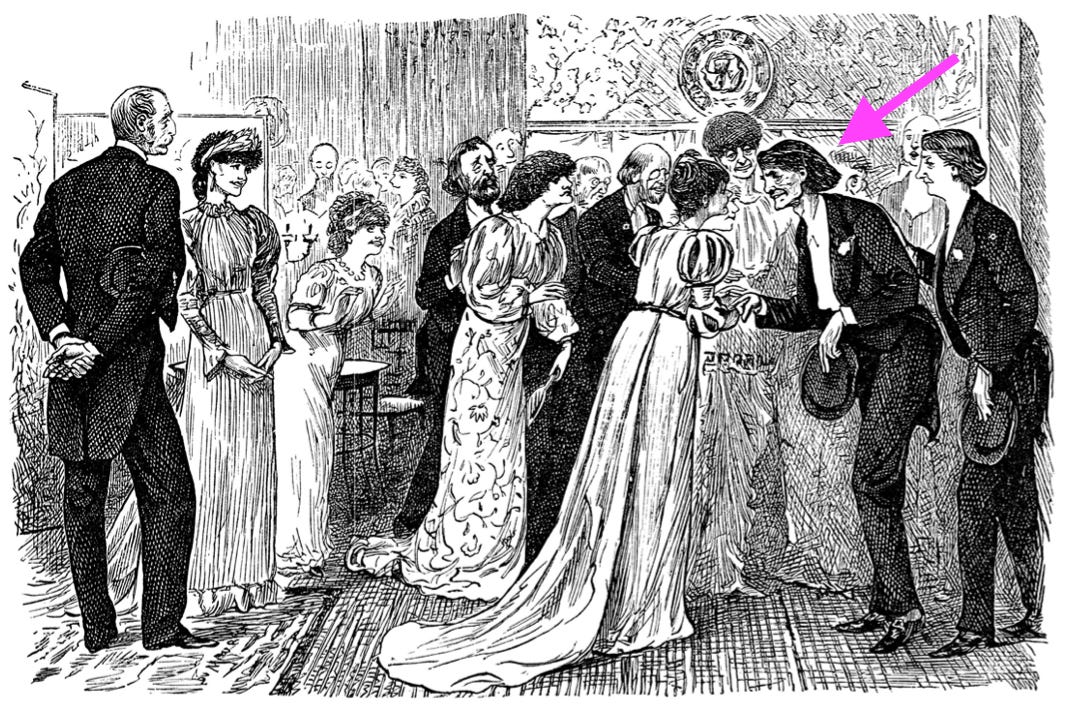

In 1880, Punch magazine published a cartoon mocking the “aesthetic poet” of the day, with his “grand head and poetic face, with those flowerlike eyes, and that exquisite sad smile.” To which Oscar announced, it me!

The cartoon wasn’t modelled after Wilde, but it was an opportunity. “By taking the generalized ridicule of du Maurier’s caricature and accepting it as a personal tribute,” Sturgis writes, “Wilde was seeking to draw a bright, clear beam of attention to himself.”

He began tailoring his quips to the press, revelling in the attention. When he was laughed at on the street, he declared “I am glad to afford amusement to the lower classes.”

The surest sign that this worked came in a series of popular plays featuring glosses on this character, most notably Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience. Wilde was conspicuous in the opening-night audience, where he “had to bear a considerable amount of chaff” with “remarkable nonchalance.” Bring on the chaff!

“If I were not a poet, and could not be an artist, I should wish to be a murderer,” he told a group of newspapermen over drinks. “Better that than to go down to the sunless grave unknown.”

The crowning achievement came from the actual crown. The Prince of Wales invited him to dinner because, as his royal highness quipped, “I do not know Mr Wilde, and not to know Mr Wilde is not to be known.”

4. Sun God of the American stage

But Oscar still hadn’t actually, you know, done anything.

Wilde’s fame was enough to get him an audience in New York City as a promotion for Patience, so across the Atlantic he went. His first lectures were uneven, filled with more art theory than quips. After he bombed in Philadelphia, his host gave him some advice on the American audience: “They care little for the abstract, the rhetorical, the remote. But they are extremely ready to recognize and applaud the immediate, the practically useful.”

To his credit, he punched up his material. By the time he made it to San Francisco, a local paper calculated his appeal to audiences as follows:

30% were determined not to be convinced by Wilde’s “tomfoolery”

13% came because their “wives insisted”

10% wanted to hear what Wilde had to say

10% had “various other reasons”

9% “wanted to see and hear the Damphool on general principles”

1% were “honest admirers of Oscar”

He went on to give more than 140 lectures across the continent, meeting everyone from Walt Whitman to Thomas Edison, and becoming “more interviewed and more paragraphed than any other figure in the country.”

Returning to England, he married, had children, realized family life wasn’t his thing, started writing more regularly, finally lived up to his decades of hype, and set himself up for his tragic downfall. But before he created any of his great works, he had to create Oscar Wilde.

He hadn’t actually been the model of Jellaby Postlethwaite, nor had he paraded down Piccadilly with a lily in his hand, as had been reported. But as he accurately quipped:

“The great and difficult thing was what I achieved — to make the whole world believe I had done it.”

Quick quips; lightning

“I’m never going to be famous. My name will never be writ large on the roster of Those Who Do Things. I don’t do anything. Not one single thing. I used to bite my nails, but I don’t even do that anymore.”

— Dorothy Parker

“It is sobering to consider that when Mozart was my age he had already been dead for a year.”

— Tom Lehrer

“Things mount up inside one, and then one has to perpetrate an outrage.”

— Muriel Spark

Speaking of...

Oscar’s formulae

Another misunderstood Great Wit

The tomfoolery of GWQ No. 123 will convince more than 40% of you, based on historical open rates. I was pleased to learn Wilde academics refer to themselves as Oscholars. Let me be the first to Cansplain that Sturgis describes Wilde’s visit to “Moncton, Nova Scotia.” I’d included some of the above in Elements of Wit: Mastering The Art of Being Interesting. Sidestep the sunless grave unknown by tapping the❤️ below.