“What ho!” I said.

“What ho!” said Motty.

“What ho! What ho!”

“What ho! What ho! What ho!”

After that it seemed rather difficult to go on with the conversation.

— P.G. Wodehouse, writing in Carry On, Jeeves.

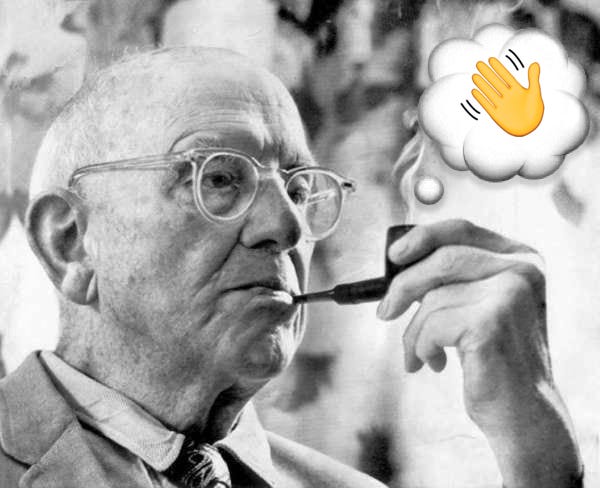

To perfectly capture this nonsensical sort of upper-crust English repartee, P.G. Wodehouse first had to escape it. The writer was by all accounts a social disaster; bad at both small talk and big talk. But boy, could he write it.

“Oh, Jeeves,” I said; “about that check suit.”

“Yes, sir?”

“Is it really a frost?”

“A trifle too bizarre, sir, in my opinion.”

“But lots of fellows have asked me who my tailor is.”

“Doubtless in order to avoid him, sir.”

“He's supposed to be one of the best men in London.”

“I am saying nothing against his moral character, sir.”

In the early 1920s, Wodehouse was stuck in London and the social life thereof. He was a member of The Constitutional Club, The Garrick Club, The Savage Club, and the Beefsteak Club, and put in regular appearances at all of them. As his biographer Robert McCrum wrote, “For a shy, private man who had difficulty with small-talk, Wodehouse was surprisingly clubbable.” The environs gave him plenty of material for his 96 (!) books, but they also kept him from his typewriter.

As he wrote to a friend: “I find it the hardest job to get at the stuff here. We have damned dinners and lunches which just eat up the time. I find that having a lunch hanging over me kills my morning’s work, and dinner isn’t much better.’

And so he developed what his friends and family called The Wodehouse Glide. It was described thusly by a friend:

“At about half-past ten — for we always dined early — we suddenly started rushing through the streets, at Plum’s prodigious pace, until a point where, just as suddenly, he had vanished and gone. No lingering farewells from that quarter. I might hear him saying Good-night, from the middle of the traffic; I might catch a glimpse of his rain-coat swinging across the road. But the general effect was that he had just switched himself off.”

There are many synonyms for this move — the French Exit, the Irish Goodbye, the Insert-Nationality-Here-Disappearance, ghosting — and as rude as it may seem, it’s far superior to the alternatives. Do you really want to go over to your host, thank them effusively, and thereby let everyone in earshot know that the party’s over? Admittedly, it’s harder to do and conspicuously ruder in a one-on-one situation.

Which may explain why Wodehouse’s famed butler Jeeves was always finding new ways to quietly enter and exit a room.

“As every Wodehouse aficionado from England to India—where he is exceedingly popular—knows, Jeeves never walks. He materialises or shimmers or floats or glides or slides like a liquid mix of eel and ectoplasm,” The Economist wrote on what would have been the author’s 100th birthday.

Ultimately, the best way to master your own version of the Wodehouse Glide is to follow this description of Jeeves’ exit:

“He seemed to flicker and wasn’t there any more.”

Quick quips; lightning

“Certainly, there is nothing else here to enjoy.”

— George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), on being asked if he was enjoying himself at a particularly dull party.

“There is nothing in Christianity or Buddhism that quite matches the sympathetic unselfishness of an oyster.”

— Saki (H.H. Munro, 1870-1916); to which the bashful shellfish says … nothing.

“At heart he was misanthropic and gifted with the sly, sharp instinct for self-preservation that passes for wisdom among the rich.”

— Evelyn Waugh (1903-1966), describing another one of his suspiciously autobiographical characters.

This concludes the 22th issue of Get Wit Quick, a weekly — hey, where’d you go? At least tap the ❤️on your way out!