If you crossed Bertie Wooster with Sherlock Holmes, you’d get a helluva lot of tweed. You might also get Lord Peter Wimsey.

Lord Peter is the aristocratic detective created by Dorothy L. Sayers, though she took credit in a roundabout way:

I do not as a matter of fact remember inventing Lord Peter Wimsey … He walked in complete with spats and applied in an airy don’t-care-if-I-don’t-get-it way for the job of hero.

This is hard to pull off via LinkedIn, but you have to remember that Wimsey landed this gig in the Jazz Age, first appearing in the 1923 story Whose Body? This was the mythical era when the idle rich solved murders in their spare time.

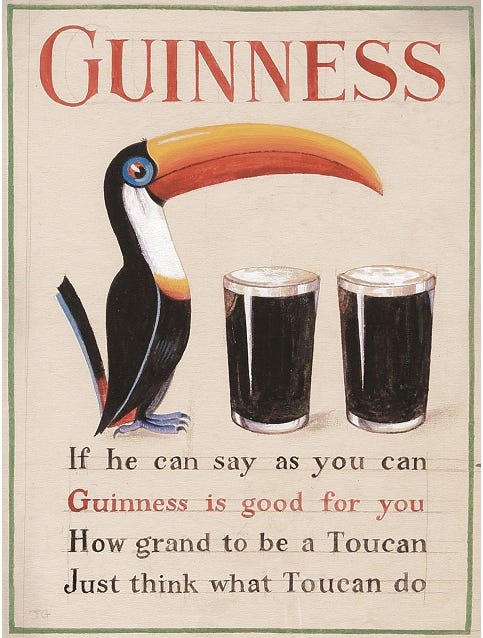

Sayers was known as The Queen of the Golden Age of British Mysteries, and it’s often said she’s a better line-for-line writer than Agatha Christie. If you’ve ever found yourself looking at the decor of an Irish pub, you’ve read her work: She began her career as an advertising copywriter and much of the “My Goodness, My Guinness” campaign was her doing, including this memorable ode to the two-pint solution illustrated by John Gilroy:

Sayers transitioned effortlessly from copywriting to crime writing, notably merging the two in Murder Must Advertise, in which Lord Peter goes undercover at an agency as a junior associate named Death Bredon.

The gentleman detective’s secret was that he was a genius disguised as a fop, hence the Holmes-Wooster crossbreed. He wore a monocle and kept his formidable powers of deduction “cloaked in the sacred duty of flippancy,” meaning that his Omnipotent Whodunit Detective Speeches are interspersed with puns, nursery rhymes, wordplay, and nonsense — all of which makes him more effective as a detective and more entertaining as a character. He breaks the fourth wall by considering his appearance in his first appearance:

Can I have the heart to fluster the flustered Thipps further—that’s very difficult to say quickly—by appearing in a top-hat and frock-coat? I think not. Ten to one he will overlook my trousers and mistake me for the undertaker. A grey suit, I fancy, neat but not gaudy, with a hat to tone, suits my other self better. Exit the amateur of first editions; new motif introduced by solo bassoon; enter Sherlock Holmes, disguised as a walking gentleman.

The lesson in Sir Peter Wimsey and his creator comes back to the sacred duty of flippancy. Just because you’re solving a murder, it doesn’t mean you can’t have some fun. Who knows: It might even help your case.

Sayers’ skill at both mysteries and marketing comes back to her ability to create clear rules and then insert the flippancy between them. In addition to the toucan poem, she thought up the Mustard Club, a clever condiment campaign that is, in today’s ad-speak, an example of a “fluent device.” The rules of the club stipulated that “every member when physically exhausted or threatened with a cold shall take refuge in a mustard bath,” among others, and they were funny, memorable, and sold many bathtubs full of mustard.

She went from creating the Mustard Club to co-founding The Detection Club, a group of mystery authors who aimed to raise their genre in the eyes of the reading public. She was serious about her craft — but again, the way she communicated that seriousness was full of silliness. To that end, Sayers composed the following oath for new members:

Do you promise that your detectives shall well and truly detect the crimes presented to them using those wits which it may please you to bestow upon them and not placing reliance on nor making use of Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo Jumbo, Jiggery-Pokery, Coincidence, or Act of God?

To paraphrase the advice they give gamblers: Set an ambitious limit and play freely within it. Besides, any good barrister knows jiggery-pokery won’t stand up in court.

Quick quip; lightning

“Here lies an anachronism in the vague expectation of eternity.”

— Dorothy L. Sayers’ proposed epitaph for Lord Peter Wimsey.

Link link, nudge nudge

“But this is a Western. Reacher confronts his feelings, finds nothing at all, and hops on the next bus out of town.”

— Malcolm Gladwell’s new foreword to Killing Floor, the first in Lee Child’s Jack Reacher series, is a classic Gladwell G.U.T. Punch: A Grand Unified Theory of Mysteries/Thrillers. He sums them up by the cardinal directions:

In a Northern, “our hero works to perpetuate order from within a functional system.”

In an Eastern, “our hero works to improve and educate the institutions of law and order in a world where they are incompetent.”

In a Southern, “our hero restores order to a world that is hopelessly corrupt.”

And in a Western, “our hero comes to a world without justice or law, and establishes order.”

That was Get Wit Quick No. 66, your weekly motif introduced by mumbo jumbo. For the record, the charter members of the Mustard Club were Miss Di Gester (secretary), Lord Bacon of Cookham, Master Mustard, the Baron de Beef, Lady Hearty, and my personal favourite for the sheer audacity of his inclusion, Signior Spaghetti. Even if some fiend tore out the last page of Elements of Wit: Mastering The Art of Being Interesting, you would still know that Idunit. Fulfill my vague expectation of eternity by nudging the ♥️ below.